From Japow to Japavalanche

Lessons learned from an unusual season in Hakuba

Image Konrad Bartelski

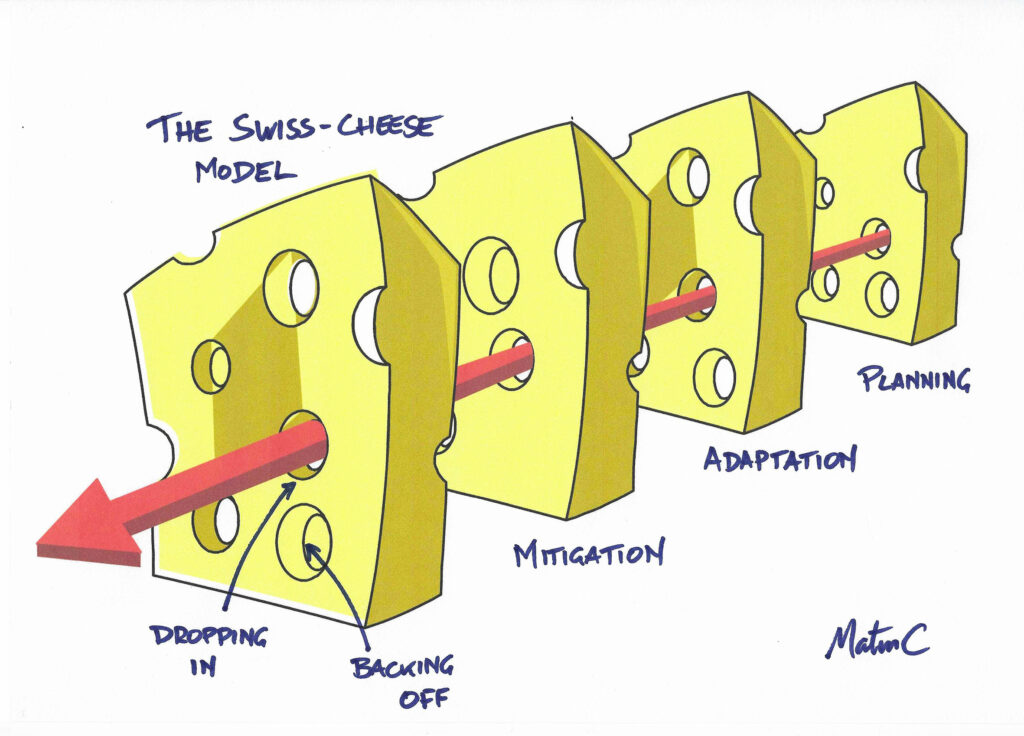

Why do highly experienced, trained (and possibly even qualified) people still have seemingly dumb accidents? Decision making in avalanche terrain is a ‘wicked problem’: “a problem that is difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognise”.

I’ve spent my career trying to learn the lessons from others’ mistakes in the hope that it will help me to ‘recognise’ these factors and hopefully avoid them myself. Watching Solving for Z inspired me to believe that, when it was my turn to have the dumb accident, it’s only right and proper to share every single lesson – which I am doing for your benefit now…

I’m not proud of this incident, and please don’t mistake me being comfortable to share valuable lessons with any kind of comfort in what happened. But if you are going to stick your head regularly in the lion’s mouth, sooner or later it’ll take a bite. It’s all about how you deal with the aftermath.

If someone had described the end-of-trip scenario to me at the start of the week, I would not have believed it was possible. But avalanche incidents are rarely a single trigger and more often a cumulative thing – several minor things adding up to the final straw.

HAKUBA, JANUARY 2020

Day one saw us rocking up, slightly jet-lagged, in a very lean Hakuba. But already the ‘worst winter in years’ was being buried by the biggest dump of the season. Our team had employed the services of a local guide (THE local guide) who came highly commended to find us the goodies. Very much the local hero, we will respectfully call him LH, for short.

Lesson 1: Being jet-lagged (or even just tired, hungover, or sub-optimal in any way) uses up valuable mental bandwidth – leaving us less for decision making in the heat of the moment. Factor this in and take it easy!

Heading up the rope tow in a blizzard, we skinned off in waist-deep powder, sticking to mellow angles among the birch trees while we found our feet. The snowfall was everything we had come for – yet it was burying some layers we had not arrived in time to witness.

Day two was our first foray above the treeline and our first visit to Narnia (a legendary sector of the forest). Thinking back, I was surprised to bottom out on hard snow occasionally on the higher slopes. Ordinarily, I would have picked up on this instantly (as a subtle sign of wind transportation over the old hard base) but jet-lagged and trusting in the ‘expert halo’ I saw around LH, I missed the full significance at the time. All was going well and we were loving it.

Subsequent days all had their moments: all minor, but all important red flags that added up. LH was clearly used to sailing closer to the wind than I, but everything seemed well considered and well managed, so I was prepared to defer to local knowledge to settle any doubts.

Lesson 2: We all have our own risk threshold, but don’t mistake good luck for good judgement!

By day five we had built up to some seriously big scenery on Happo One in the high alpine. Cutting the slope, LH demonstrated there were clearly instabilities, so skiing one at a time and stopping in sensible safe places felt increasingly critical.

We had become all too accustomed to the hotel driver or cook joining us as tail-gunner – albeit they were mostly super helpful and well disciplined. But when one of the backmarkers set off, while one of our team was still in the gully, the fine line between sluff and a veritable slide became all too blurred.

This was a step too far and I was furious: taking it to the edge was just about okay – so long as we were disciplined about safe travel. But adding an over-hasty additional load to such a sensitive snowpack took us over the line.

Harsh words were exchanged in private; a robust briefing for the final day was exchanged with the whole team, before we hopped in the vehicles. The message was simple: we had taken it close enough – but no further. We now knew there were weak persistent layers in the pack – so the only way to ski safely was to stay on sub-25-degree slopes and ski with discipline (in sight, one at a time, stopping only in safe places).

Lesson 3: Far better to risk being a downer, than a danger!

We headed out for the final day of the trip. Just watch how, step by tiny step, we deviated from the plan…

Putting our skins on, we met a team of LH’s mates, intent on joining us. Far from happy, I was reassured that they were simply planning to use our skin track – and keep their distance. So, reassured, we skinned off to access the first big descent.

A quick check of the stability confirmed the snowpack was good; the gradient erred on the right side of safety and the team knew we had to keep our discipline.

One at a time, we feasted on our individual share of the plentiful bounty. Before meeting up on the safe flat glade in the forest, to put our skins on for the second lap. Our cautious approach was being rewarded, but we weren’t the only ones reaping the rewards: LH’s mates had caught us up for a spot of lunch. It made for a super-sociable picnic before we made our way back to the top of Narnia.

While this pitch was ever-so-slightly-steeper than the previous slopes, we had skied it just a few days ago, so we knew there was no persistent weaknesses there. Besides, we left it properly ploughed with waist-deep furrows all over it, now covered in just enough powder. This was hardly going to result in more risk since our last visit! Fully confident in the plan, I hung back to support the back-markers, leaving LH to beat the track.

Our arrival at the top of the pitch coincided with an unexpected spike in temperature. Unnoticed by us, the snow was stripping off the sunny side, while we were blissfully unaware in the shade. But an unforecast change in temperature produces an unexpected change to the avalanche risk, which was rapidly rising with the heat.

Our plan so far had gone so well. Everything had been super stable all morning (but of course – it was easy angled and we never put more than one skier on it at a time). This was cause for confirmation that we were doing the right things, and not a reason to relax. A classic blunder!

Lesson 4: Stick to the plan!

For us, this was the perfect storm: I expected us to ski the same line as before, with the same discipline that had worked so well all morning. But we let our guard down, just as we added the extra players to the mix and as the temperature went through the roof. Back on a familiar slope, our team fanned out to find fresh snow. With the increased demand, some strayed onto virgin snow that had not previously been skied, and still harboured that weakness.

Lesson 5: There is no such thing as security in numbers: more people, more load, more pressure to spread out.

The rest all happened so fast, and with that eerie silence that anyone who knows, will recognise. A shallow (30cm) crown wall was enough to carry Mike and Jim down the slope. A short slide, but a significant volume of snow, meant this was instantly serious enough. The radios crackled to life and, gathering the rest of the team, we safely skied the planned line. The years of training kicked in, and we quickly established the team were all accounted for.

Lesson 6: Radios for techy tree-skiing are key. We had four in the team. Made it really easy to check in, get a headcount and get up to speed on the plan.

Mike was mostly buried, but amazingly unshaken (although we never did find one of Mike’s skis, despite extensive probing). Jim had badly tweaked a knee. But the fear the whole team experienced (and the lessons we learnt) will last far longer than any of that. Once you trigger a slope, you are instantly completely and utterly out of control. It all happens so fast – and the difference between walking away and losing the whole team is so tiny that it is genuinely frightening. The full consequences largely depend on your behaviours and positions in that instant.

Lesson 7: The gap from near miss to complete disaster is smaller than you think! So always be ready…

Literally limping back to the resort, we all recognised that it could have been so much worse – if we hadn’t been so conservative, we could have been in the high alpine, rather than tree line. We subsequently discovered that spike in temperature triggered several unexpected slides. Others were not so fortunate.

We might have reduced the risks, and the consequences, all day – but this was still WAY closer to the limit than I ever want to get again. So many humbling lessons to learn. If this article saves just one avalanche incident it will have been worth sharing.