Want to know why those deep crystals and weak layers are such a big deal? Welcome to Martin Chester’s snow science class, here to help you learn all about snow and how to avoid it sliding…

Imagine the snow is lapping down outside. Huge flakes of powder, undisturbed by the wind, are floating down like duvet feathers of pure joy. Pyramids of fluff are piling up on the branches; pillows forming on every boulder; and tomorrow is going to be a great day.

It may be an overhead blower tomorrow, but in a week’s time we will be gagging for another dump. With early season temperatures well below freezing, where does all that beautiful powder go? The truth is that only a tiny percentage ever melts and makes it into the rivers. The rest goes through a process called sublimation. This is where the icy crystals go from being a solid to being a vapour without ever becoming a liquid.

So what? Well if you understand the basics of how snow can settle, change shape, lose its grip, and build new crystals, then it opens up the way to understanding how to spot the risks, and how to find the finest fields of fresh. So read on…

CRYSTAL SCIENCE

Those duvet feathers are pretty light and fluffy in the world of crystal science. As they carry little weight, they apply very little pressure, so there is very little to stick them together. Blow a pile of powder and each flake floats away like the seeds of a dandelion. With each flake having very little impact on the next, they tend to represent low avalanche risk. They may sluff off the steeps, but there is nothing cohesive about them, and very little chance they will trigger anything bigger.

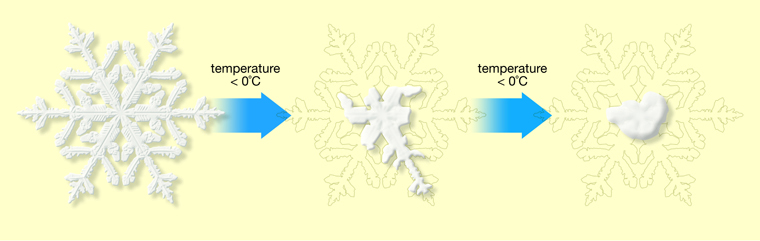

But those crystals of purest pow are going through a transformation, called ’rounding’, as they turn from fingery fronds to fist-like nuggets, before bonding together. When they first round, these fluffy crystals lose their grip on one another. Slopes that were only just clinging on, slide off, causing a spike in avalanche risk.

To tell when, just look at the trees. Our ancestors knew that snow settling on branches means that the snow is settling on the ground. All of a sudden, after a big dump, all the branches in a certain area are sloughing their loads, seemingly in unison. This is due to every crystal rounding off until it has no grip. Like food going off – if you leave it out in the sun it will go off quicker. Leave it in the deep freeze and it will last longer. But it will still go off: and when it does, it is a safe bet that all the slopes of that height and aspect are less stable. The good news is that things rapidly start to settle down from then on. So watch out for the signs.

SNOW THAT GROWS – NOT FALLS

It’s December, and the temperature is -20˚C. The powder is awesome, but limited, and that’s how it could stay for weeks. The winds come and go, blowing the snow about a bit, but while we wait for more snow to fall, these cold temperatures can grow icy crystals that will come back to haunt us later in the season. These are nothing like those feathery flakes. These are more like the crystals you grew in your chemistry set as kids.

Because they are crystalline, they don’t stick together well, and they don’t round off and bond together as readily as those delicate flakes. Some grow on top of the snow pack, only to be buried later (surface hoar), while others grow deep within the snowpack (depth hoar) rotting the foundations in a time bomb under any new snow.

SURFACE HOAR

The winter equivalent of dew. The moist and humid air cools overnight and grows crystals on the top of the snow pack. They are pleasant to ski and no problem for now – but they become a danger when buried, as they form a slidy, icy layer to stop new snow from sticking to old.

Surface hoar forms all over the hill, but is quickly destroyed by any sun, wind or warming so they mainly persist on shady steep slopes. After a spell of cold calm days they will have built up in abundance. So, once the snow finally arrives and you are mad to ski the new powder, the crystals lie under the snowpack, in the greatest quantities, exactly where you are going to head first!

DEPTH HOAR

Long cold spells on early winter snow should ring alarm bells. As moisture from the ground meets the penetrating frost from the air, crystals grow deep down. This is depth hoar. They develop a caster-sugar consistency, then grow and become more crystalline until a layer of in-cohesive cup crystals are formed. Enjoy that early season powder while it lasts – that weird sugary texture is the dodgy foundation of tomorrow.

In the simplest terms, depth hoar is a bit like surface hoar but the other way up. The snow is like a giant blanket of thermal insulation over the ground. If it is shallow, and poorly insulating, the warm moisture of the earth meets the cold temperatures from the air, and the crystals start to grow.

RISK FACTOR

So in the simplest terms: long cold spells + shallow snowpack = rotten foundations. Got it? The risk is highest where the snow is shallow, so next to ridge lines and surrounding those appealing looking ‘islands of safety’ in the middle of large slopes (gulp)!

The good news is that, if you understand the process, you will also grasp that they are less likely to form where the ground is well insulated by deep snow and less likely to form where there is no source of ground moisture (permafrost and glaciers). But, bear in mind that these little blighters can grow anywhere there is a rapid change in temperature in the snow pack, like a warm, damp layer next to an icy, dry, crystalline layer. These crystals are likely to grow where the two join. The result? A layer of ball bearing like nuggets between layers within the snowpack, and the perfect shearing layer: for any fresh snow above is not bonded to the layers below.

UNDERSTANDING SNOW PROFILES

Stick to the basics: think of a seasonal snow pack as a building project: you want strong foundations; you want each layer to be well bonded to the next; and if the layers get progressively softer towards the top, that is good. As these layers can be hard to see, you just need to know that prolonged cold temperatures, and radical changes in temperature, are bad news.

SNOW PROFILES & BETA

One way to find out all the info is to dig a hole. Dig one in a deep place, and one in a shallow place. If you find that sugary stuff in shallow pockets, then you can be sure that all similar shallow areas will have dodgy foundations for some time to come, and avoid them accordingly.

If you want to track their progress, look up ‘schneedeckenstabilitat’ (snow pack stability) on the Swiss Avalanche Institute website. You can also find plenty of data from holes dug by pros all over the Alps, on avalanches.org.