WHAT’S IT LIKE TO KITE SKI 2600KM ACROSS GREENLAND?

The Greenland icecap offers incredible opportunities to those who wish to test themselves with a long-distance expedition, in this case, kite-skiing 2600km from south to north Greenland. It was the first time I had been asked to undertake this particular trip and in turn guide two people who had not been on an expedition of this kind before either, Bjørn Wills and Eric Leegwater.

It’s not necessarily the most difficult expedition but there is large cost involved, and the kiting element certainly isn’t for everyone… However, the challenge was gladly undertaken by Bjørn and Eric. Both men, from Denmark and the Netherlands respectively, had different skiing and kiting experience, but they also embarked on the necessary training to give themselves the best chance of completing the journey.

With a trip like this you want two things: good weather and good katabatic winds. To give us the best chances of catching both I set the start date in early May, beginning in the fjord-side settlement of Narsaq in South Greenland.

“Standard Polar travel is slow and monotonous – add a kite into the mix and you suddenly have the freedom to move fast”The expedition was to be completely unsupported and therefore being prepared for all eventualities was imperative. This involved packing enough food to sustain the three of us for up 40 days (we hoped to complete it in 32-38, weather allowing), plus clothing and sleeping bags that could withstand temperatures plummeting to -35°C, GPS navigation devices, satellite phones and… a gun. Yes, carrying a weapon is a requirement of Greenland authorities in case of encounters with polar bears (after our first day we came across fresh prints of a bear that thankfully we did not encounter…).

Kit wise, we used our biggest kites with 50-metre lines to catch even the lightest of winds. Then, of course, there are the skis and boots. On my feet were ski touring boots (Scarpa Freedom SLs), lightweight Dynafit TLT Speed bindings and a Rossignol Hero Master Factory race ski.

After a few days in Narsaq preparing for our journey we got the go-ahead to sail out to the glacier that would be our gateway to the icecap. After being dropped off, we were completely alone, left to make our own way across the stark and often unforgiving landscape. The first challenge was having to carry all the equipment up a steep rocky slope before we reached the ice. Due to the terrain, we used a rope and pulley system to shift the 110 kilos we were each carrying on our pulks. This took an arduous two days – pausing only to camp on a snow patch – but by the third day the wind was on our side, and we could start to kite the first leg of our journey across the ice: a 600km stretch to an abandoned radar station.

Standard Polar travel is slow and monotonous – add a kite into the mix however and you suddenly have the freedom to move fast (reaching speeds of up to 45km per hour) when the wind is good, and the fact the winds are constantly changing adds another dimension too. The hardest part is staying on your feet all day while holding an edge – it gives a new meaning to ‘thigh burn’. Oh, and the learning part – there can be some big falls and unintended jumps. When the light is poor it is also common to fall over; it’s like kiting in the inside of a ping pong ball!

The first four days of our excursion were fairly uneventful but quite slow going – we only covered 25-40km per day due to light winds from the wrong direction. From day four the wind began to pick up, but on day five a storm settled in and halted our journey for 40 hours. The visibility was zero with winds of 40 knots, far too strong for kiting! There was nothing to do but make camp and wait it out. We passed the time by playing cards, resting, eating and digging the camp out so we didn’t get snowed in.

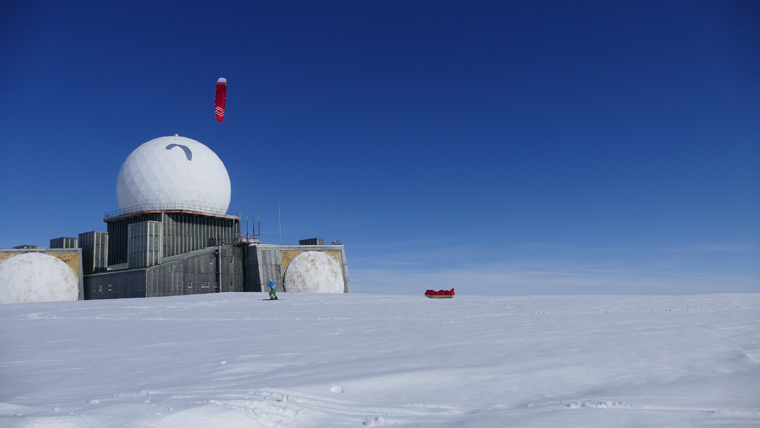

After the storm had died out we begun the second leg to the radar station. And on day 12 we arrived at the US early warning radar station, used during the Cold War. Abandoned within two hours in 1988, there are still coffee cups left on the side and pots on the stove. The 200ft high radar dome protruding from the building is a marker on the landscape and the station became a highlight, albeit a slightly surreal one, of the trip.

At this point in our journey we still had 1700km to cover, heading further north to where the sun no longer sets. The weather had become more favourable though and the snow conditions were better (not so many lumps and bumps, which can be hard on the knees), so we were able to kite greater distances, around 100km a day (with 210km being our record). With constant light, you can kite as long as your legs will hold you. Days fall into a rhythm of: wake up, melt snow, eat as much as possible, pack up, kite for up to 10 hours with a few short breaks, set up the tent, eat as much as possible again and sleep.

All the while it was just us and the remote landscape – plus a few snow buntings (small birds, often called ‘snowflakes’) for company.

The sledges were getting lighter due to food consumption, and apart from three days battling sastrugi, progress was good. On day 17 we woke up to a pretty unusual phenomenon on the ice cap called a fog bow. It’s similar to a rainbow but the water droplets on the ice cap are much smaller, so it creates a white ring rather than the more familiar coloured one. Visibility became an issue again, so it was important to kite close together – you can very quickly become parted by a few kilometres and find yourself lost. At this point we were kiting with a chill factor of -25°C, which I’d still consider to be good conditions.

We arrived in North Greenland after 27 days and 2620km of kiting but still had to make the steep descent down Bowdoin Fjord. Once back at sea level, we completed our journey to Qaanaaq with the assistance of local hunters and their dogsleds. We were happy to sample a few beers and a normal bed!

I am always left with mixed feelings after an expedition like this – happy that we had made it to the end in one piece and as friends, but sad that it was over. You commit so much time and energy to make these expeditions happen that when it’s all over you feel like there is something missing – until you start plotting the next adventure that is.

Sound like something you’d be up for? Find out more at expeditions365.com